How Ivy League Style in Ametora Influenced My View On Fashion

The influence of Japanese style in today’s global fashion market is certainly evident on a global scale: when viewed at surface level, mainstream fashion brands UNIQLO and Muji are among the world’s leading companies that have now spread to over a thousand branches located worldwide. I’ve been a fan of Uniqlo since I discovered the brand during a trip to Singapore in 2012 when I was only a Sophomore in High School; I probably attribute that memory as the first time I got into Menswear, as I instantly fell in love with the clothes they were offering—high quality and stylish, yet at an affordable price point.

If you haven’t heard of Grailed before, and you have the slightest interest in menswear, I suggest you visit the site and browse the articles of clothing posted by people and discover styles of brands you’ve never heard about before.

It’s easy to stop there and call it a day, but throughout my style journey, I found myself getting less interested in buying clothes for the brand name and more interested in the history of particular brands and the culture they represent. A few months ago, I started reading menswear retail site Grailed’s Dry Clean Only blog platform where they post articles that feature brands such as Raf Simons and Supreme. While browsing the different articles on Dry Clean Only, I came across an article about the Osaka 5 denim brands which included a part about Ivy Style in Japan, which led to an article about Kensuke Ishizu who started the Ivy League style movement in Japan around the time when they were just recovering from World War II—it was at this article where I found out about the book Ametora, and I’ve been obsessed with Japanese fashion ever since.

Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style is a book written by W. David Marx who is a Tokyo-based author specializing in Japanese Fashion, Music, and Culture. While the book focuses on the origin of Japanese Fashion and how it eventually influenced other countries’ styles globally, Marx wrote the book as a “vivid case study on how trends form, why some fads become traditions, and how globalization really works.” Ametora is a Japanese slang term that means “American Traditional” and we will see how this term came to be in this blog post. Marx’s book is considered the definitive book about Ametora by the entire Men’s Fashion community including G. Bruce Boyer (author of True Style), Mark Cho (co-founder of The Armoury NYC), and online menswear forums such as Style Forum and the Male Fashion Advice subreddit.

As said above, the term Ametora originated from how the Japanese were influenced by American Style starting as early as postwar Japan with Ivy League style and later putting their own twist and establishing a style of their own with Ura-Harajuku brands such as Nigo’s A Bathing Ape (Bape) and Hiroshi Fujiwara’s Goodenough in the 90’s—Japanese denim brands Kapital and A Flat Head also fit this description by showcasing Japanese quality and craftsmanship in replicas of vintage American jeans. The book was split into ten chapters that discuss each style separately but collectively made me understand more than just how the Japanese dress. With that said, the chapters that made the most impact on me were about Kensuke Ishizu and Ivy League Style.

Kazuo Hozumi’s illustration of the “Ivy Boy.”

“I don’t really know what ‘Ivy’ means—but it’s cool right?”

Kensuke Ishizu, Ivy Style, and VAN Jacket

Kensuke Ishizu founded VAN Jacket in the early 1950s soon after the Americans left Japan after World War II (The Occupation) when he decided to create American style ready-to-wear clothing and offer it to middle-class Japanese citizens. At the time, Ishizu was probably the only person in Japan who had a good grasp on what American style was: he grew up around the time when Japan was transitioning to a more modern culture by adopting western traditions and he also experienced the culture in Japan right after the war when Japanese people suddenly became obsessed with anything that was American.

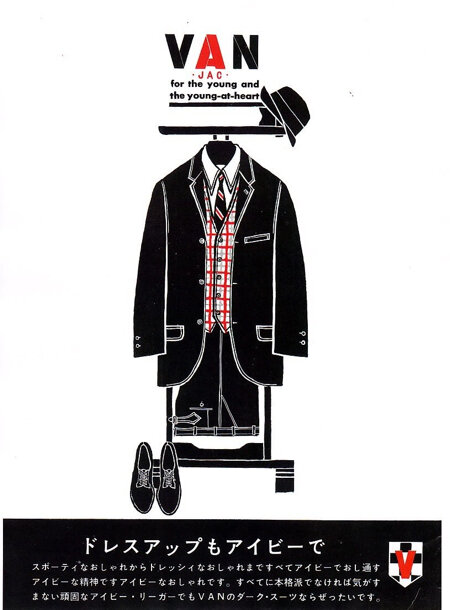

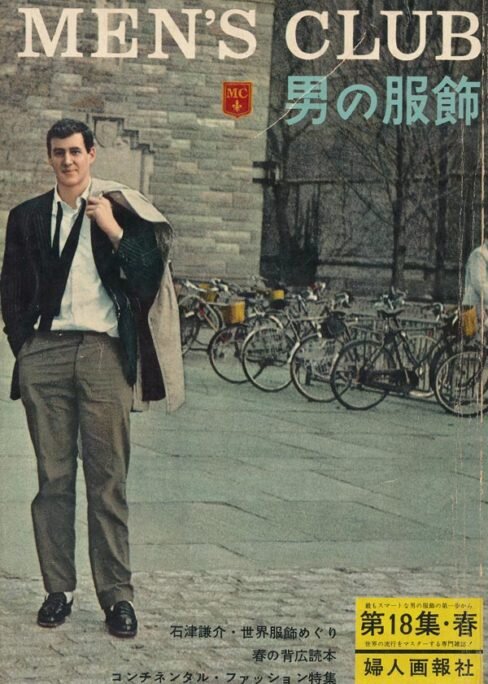

It wasn’t long after he started VAN when he joined the editorial team at Otoko no Fukushoku (“Men’s Clothing”)—a publication offering step-by-step guides on the proper way to wear semi-formal and business attire—which was later renamed to Men’s Club. VAN Jacket then started selling what Ishizu dubbed as “Ivy Style” after he heard about what college students were wearing around Ivy League campuses in America from a soldier he met during World War II named O’Brien. Ishizu noticed that he wasn’t getting a lot of sales by selling his clothes to the middle-class, so he decided to target the youth, which started the Ivy Boom in Japan.

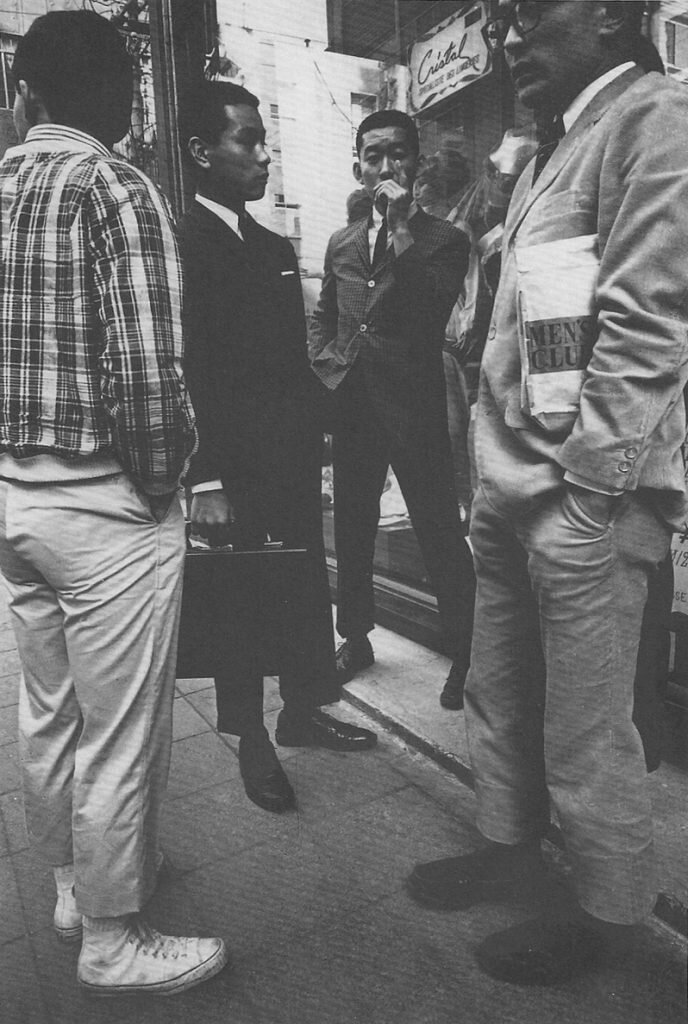

Suddenly, the youth in Japan wanted to wear Ivy League Style clothing. Through Men’s Club, Ishizu wrote step-by-step articles teaching readers how to properly wear Ivy. The catch was, Ishizu never indicated that he was writing the articles in an attempt to self promote VAN Jacket (it worked). VAN Jacket was experiencing unprecedented sales at the time, but a new problem arose: parents were associating Ivy League Style with delinquency. During the Ivy Boom, tribes were formed around Ivy Style; one of the tribes, called the Miyuki-tribe (Miyuki-zoku), would roam around Ginza sporting Navy Blazers, Oxford Cotton Button-Down Shirts, and Khaki Chinos. Even though they weren’t committing any crimes, this was during the time of the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo when Japan was trying to prove to the world that they were a much better nation after the defeat in the war—they didn’t want other visiting countries to see these “delinquents” wearing Ivy Style Clothing and leave a bad taste.

Team Japan during the 1964 Summer Olympics Opening Ceremony in Tokyo

To convince the entire Japanese nation, Ishizu decided to design Japan’s attire during the opening ceremony of the Olympics, where team Japan wore Red Blazers with Gold Buttons, White Oxford Button-Down Shirts, White Pants, and White Shoes. Ironically, other countries had a positive reaction to the outfit but the Japanese government itself did not, and Ishizu needed another way to convince the Japanese public that Ivy Style should be adopted.

Take, “Take Ivy”, a short documentary showcasing the outfits of college students in Ivy League Campuses in the US. In 1965, eight members of VAN Jacket and Men’s Club including writer Toshiyuki Kurosu, photographer Teruyoshi Hayashida, and Kensuke Ishizu’s son Shosuke Ishizu, took a flight to the United States and went around the Ivy League campuses shooting photos/clips and interviewing students roaming around campus. When they returned to Japan, they arranged events to show the film to retailers and even the police, to convince them that this was really how American college students dressed around campus—it was because of this film that Ivy Style was widely accepted in Japan and eventually spread into the mainstream. Ivy Style became widely accepted in Japan soon after, and it eventually evolved into other forms such as Heavy Duty Ivy which combined traditional Ivy Style with rugged clothing like North Face jackets and L.L. Bean Boots.

I adopted the idea of Ivy League Style much in the same way Ivy League Style was influenced by America

What resonated with me about Ivy Style was that they were selling an entire lifestyle rather than just the clothes themselves: in Men’s Club, for instance, many articles were written about where guys should eat, how to present themselves in front of other people, and how to properly date a girl and where to take them out for a date. I’ve never viewed fashion in this way even though I already shared some common perspectives. When I started getting into fashion, I would wear brands just for the sake of wearing brands: during my freshman year of college in 2015, I wanted to own clothing from brands like Supreme and Bape for the “clout” you’d have for wearing those clothes, even though there is a deep history and culture within those brands.

Safe to say, I’m far from my freshman year self, but I’m not even close to the levels of Ivy fanatics during the ‘60s and ‘70s, or even modern equivalents such as avid fans of Supreme lining up just to be able to get the new North Face collaboration on a freezing winter’s day. Sure, nowadays I read about different brands and the values they stand for, but I now desire to have a deeper connection with the clothes that I wear much in the same way Kensuke Ishizu wanted VAN Jacket’s audience to dress.

Ivy League Style in a glance

Brooks Brothers Navy Blazer

Uniqlo Oxford Cloth Button Down Shirt

Bonobos Khaki Chinos

Alden Penny Loafer